The Winner’s Curse#

If it is true, as common sense tells us, that a lease winner tends to be the bidder who most overestimates reserves potential, it follows that the “successful” bidders may not have been so successful after all. Studies of the industry’s rate of return support that conclusion. By simulating the bidding game we can increase our understanding and thus decrease our chance for investment error.

Common Value Auction Models#

- common value auction models#

auction models in which bidders have private information about uncertain characteristics of the item being sold, rather than just about their own private values.

Three Main Issues:

The winner’s curse and the strategic bidding response

Information aggregation and “price discovery”

Selling strategies and information disclosure

The Winner’s Curse#

Having the highest bid suggests that you had one of the highest estimates compared to other bidders. If you respect your competitors’ estimates, then winning may suggest that you overestimated the value of the certificate.

Question

Suppose we model the auction as a game. What are the Nash equilibrium bids?

The Common Value Model#

Two bidders with “common value” \(v\) drawn at random from a known distribution.

Bidder 1 receives a “signal” \(s_1\) (correlated with \(v\)). Bidder 2 receives a signal \(s_2\). Signals provide information about \(v\), but not perfect. Assume \(\mathbb{E}[v|s_1, s_2]\) is increasing in \((s_1, s_2)\).

Question

How should bidders account for the winner’s curse?

How to Bid?#

Suppose bidder 2 uses strategy: drop out at \(b(s_2)\), with \(b(\cdot)\) increasing. Bidder 1 has a signal \(s_1\). Suppose price reaches \(p\). At this point, 1 can rule out \(b(s_2) < p\).

Question

Is it better for bidder 1 to drop out at \(p\) or \(p + \epsilon\)?

Solution

Makes no difference if \(b(s_2) > p + \epsilon\). Only matters if \(b(s_2) \approx p\). That is, if \(s_2 = b^{-1}(p)\).

So bidder 1 must ask: would I want to win at price \(p\)? If bidder 1 does win at price \(p\), they learns that \(s_2 = b^{-1}(p)\), so the expected value is \(\mathbb{E}[v|s_1, s_2 = b^{-1}(p)]\)

Best strategy: stay in while \(\mathbb{E}[v|s_1, s_2 = b^{-1}(p)] > p\) and drop out when \(\mathbb{E}[v|s_1, s_2 = b^{-1}(p)] = p\).

Symmetric Equilibrium#

Therefore, bidder 1’s best response given signal s1 is to bid

Let’s look for a symmetric equilibrium where bidder 1’s strategy \(b^{*}(s_1)\) is the same as 2’s strategy: \(b^{*}(x) = b(x)\) for all \(x\). Then, bidder 1’s equilibrium strategy must be \(b^{*}(s_1) = \mathbb{E}[v|s_1, \{s_2 = s_1\}]\). To find her equilibrium bid, bidder 1 should imagine that bidder 2 has the exact same signal. Her bid should be what her value estimate would be if she knew that to be true.

The No-Regret Property#

Suppose both bidders use that equilibrium strategy. Then bidder 1 wins if and only if their bid at strategy \(s_1\) is greater than the bid at strategy \(s_2\) of bidder 2, which can be expressed as:

Bidder 1’s expected value with pooled information is \(\mathbb{E}[v|s_1,s_2]\). Bidder 1’s payment \(b^*(s_2) = \mathbb{E}[v|s_2,s_2]\). Then bidder 1 is glad she won, and does not want to change her bid.

Bidder 2’s expected value post-auction is \(\mathbb{E}[v|s_1,s_2]\). If bidder 2 had bid higher and won, she would pay \(b^*(s_1) = \mathbb{E}[v|s_1,s_1]\). Then bidder 2 is glad they lost and does not want to change their bid.

The no-regret property states if bidder 1 could learn \(s_2\) and see bidder 2’s bid (in addition to \(s_1\)) before finalizing her own bid, she could not gain by revising her bid.

Common Value Bidding#

Important

In common value auction models, rational bidders account for the fact that winning or losing conveys information about what other bidders may know.

In the winner’s curse, winning tends to mean that the winner’s estimate is too high, but in other situations it can mean that it is too low! That alternative is called the loser’s curse.

Winner’s or Loser’s Curse?#

Consider two contrasting examples.

Example 10 (Winner or Loser’s Curse)

Case 1: 10 bidders, 1 item. Only the highest bidder wins.

Winner’s curse: Winning means the nine other signals were all lower.

Case 2: 10 bidders, 9 items. Only the lowest bidder loses.

Loser’s curse: Losing means the nine other signals were all higher.

Mixing Kinds of Uncertainty#

Some version of the common values logic arises whenever other bidders may have information that is relevant for your value, not just from their tastes (“private values”) being uncertain.

Suppose we’re bidding for a certificate which, for me, will pay the sum of the dots showing from ten rolls of a pair of dice. The roll of one pair leads, on average, to seven dots showing. Ten rolls leads, on average, to 70. If I’m risk neutral and nobody gets to see the outcome, I should bid 70, without regard to other bidders’ estimates, but if someone does get to see the outcome and his payoff is, say, eight times the number of dots, that is very different!

Providing Information to Bidders#

Deciding how much information to provide to bidders – for example, what information to disclose if you are selling a house, or a company – can be a tricky choice. Sometimes, sharing information about an item improves all bidders’ estimates and the associated chance that the highest-value buyer wins the auction, increasing total welfare. In addition (Milgrom-Weber “linkage principle”), seller-provided information helps players to estimate other players’ values, intensifying competition and raising prices. There are also numerical examples in which information is useful only to a single bidder. For others, sharing that amplifies the winner’s curse and makes it more difficult to estimate competition. The seller does better to withhold such information.

De Beers Diamond Example#

De Beers sells a large fraction of the world’s uncut diamonds: once 85%, currently 23%. It sells these diamonds at regularly scheduled “sights”. Each buyer, given a box of diamonds graded by the seller, must decide whether to buy the box at its quoted price. What is the rationale for having so little inspection and pricing of individual items? And no bidding?

Financial Securities Example#

Financial securities may be traded more efficiently when there is less potential for asymmetric information about common value factors. Buyer is less concerned about adverse selection (“why was that seller so eager to sell?”), and seller is similarly less concerned. Saves resources that might be spent collecting information offensively (to exploit other traders) or defensively.

Helps to understand relative liquidity of certain securities

Index funds (safer than stock-picking if insiders have good information about individual stocks.)

Bonds backed by pools of mortgages (saves needing to know about the default risk of each individual mortgage) although the 2007 financial crisis revealed some of the risks that can still be created.

Highly collateralized loans: pawn shops & repos

Information Aggregation#

Market prices can sometimes summarize the information of many traders.

Suppose we have many bidders, and each has an independent estimate \(s_i = v + \epsilon_i\) with \(\epsilon_i\) symmetrically distributed around \(0\).

The Median of the bidder’s estimates \(s_i\) can be a good estimate of \(v\). Why?

\(\text{Median}(s_i) = \text{Median}(v) + \epsilon_i \approx v\).

Important

Intuition “The wisdom of crowds”

Question

If many bidders compete in an auction, is the resulting price a good estimate of \(v\)?

Potentially YES!, auction price can aggregate information.

Let’s go through a somewhat loose sketch of the argument. Why Information Aggregation? \(N\) bidders, \(K = N/2\) items, top \(K\) bids win and pay \(K+1\)th bid.

Equilibrium bidding: bid so that if you “just” win, you’ll “just” want to win (else should raise/lower bid).

So, the auction price will be approximately the median signal!

Intuition

“Market prices can aggregate information from dispersed sources.”

Common Values in Practice#

Many auctions have some “common value” element

Timber auctions: uncertainty about how many board-feet of each kind of timber on the tract that’s being sold.

Oil lease auctions: bidders do independent seismic studies – each has valuable information about the uncertain amount of recoverable oil. Some may also have drilled nearby.

Service procurement auctions: uncertain characteristic is the difficulty of the job.

Initial public offerings (IPOs): uncertainty about a company’s people, technology, and the strength and plans of competitors.

OCS Auctions#

The US government auctions the right to drill for oil on the outer continental shelf. Value of the oil is similar for the different bidders, but none knows exactly how much oil there is (or if there is any!). Prior to the auction, the bidders do seismic studies.

Two kinds of sale:

“Drainage tract” – adjacent to a previously drilled tract.

“Wildcat tract” – not adjacent.

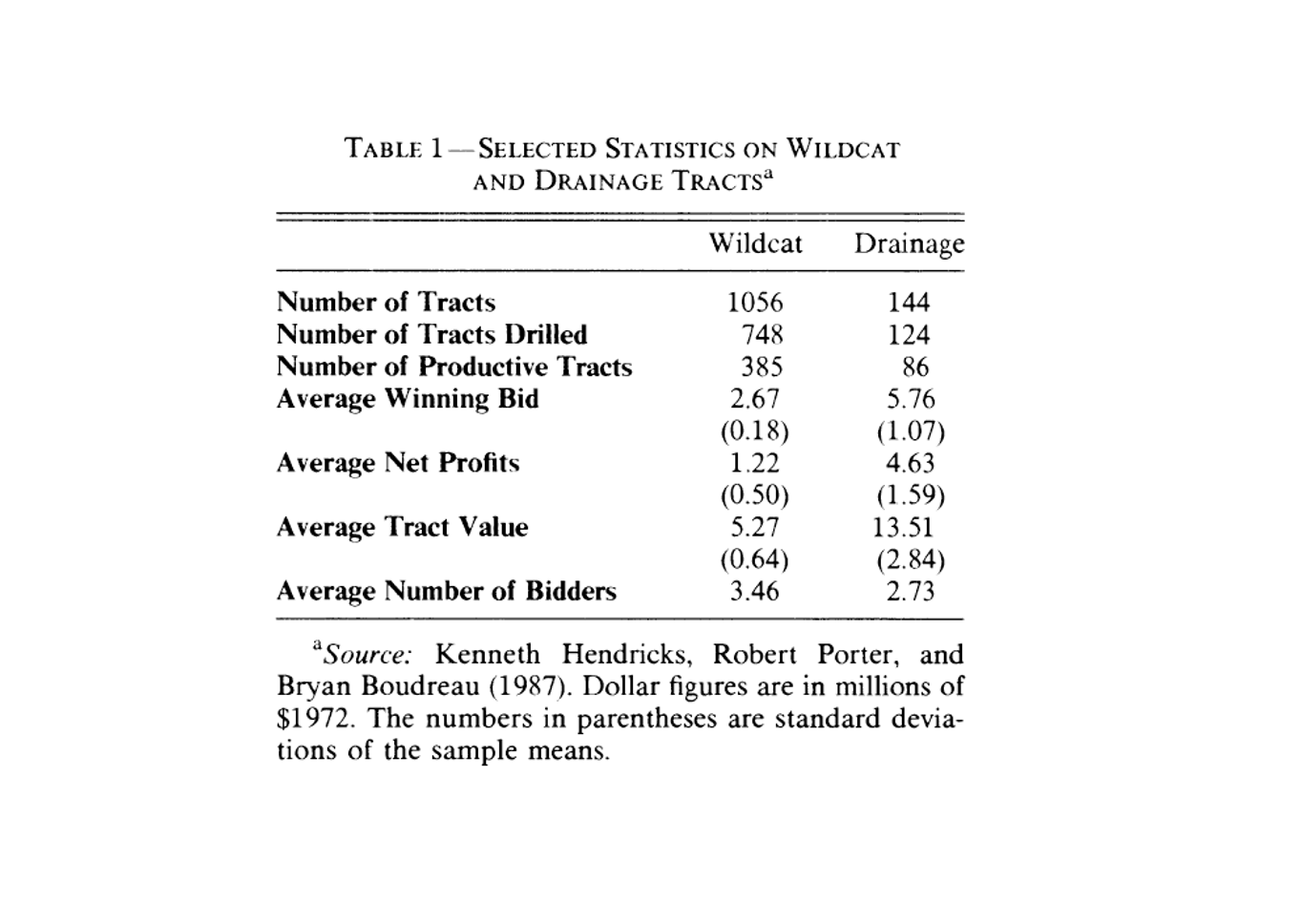

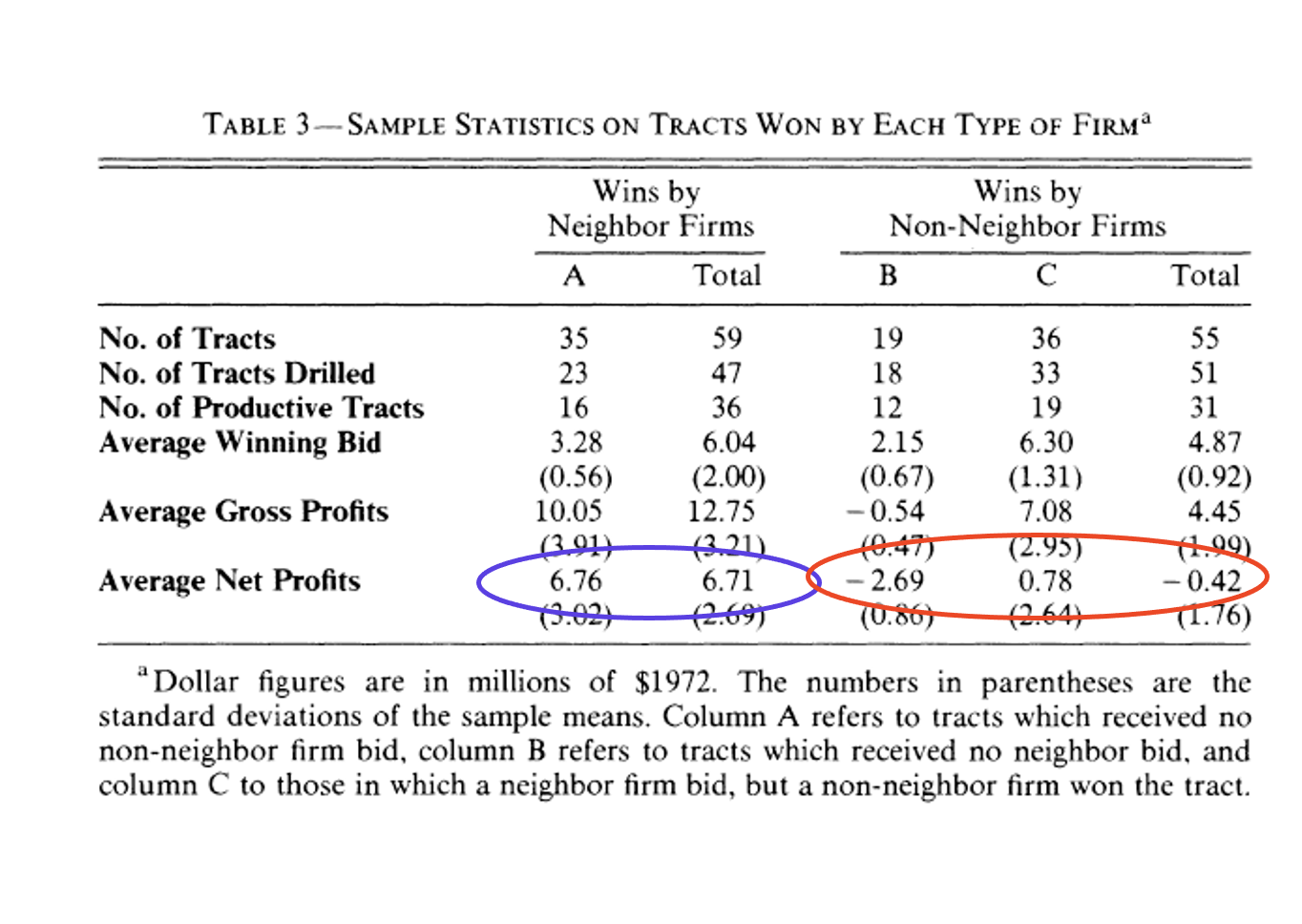

Wildcat vs Drainage#

Question

What might explain the differences in profits and participation?

Drainage sales are very profitable for neighbors, unprofitable for non-neighbors (winner’s curse). Wildcat sales yield low profits. More bidders and more effective competition

Internet Advertising#

Internet advertisers often can identify people or profile their behavior and then bid to show them ads.

Concern in some advertising auctions Sophisticated advertisers potentially can “cherry-pick” the best opportunities by bidding high only for those impressions. Less sophisticated advertisers who submit the same bid for good and bad opportunities might be left with only the bad ones.

Example: Yahoo! – Burger King’s “Happy contract”

Initial Public Offerings#

In an IPO, all buyers essentially have the same value 𝑣, equal to the stock price once trading opens.

You should want to buy in the IPO if you think the IPO price 𝑝 is less than 𝑣.

Do IPOs sell at a discount? Not necessarily. If everyone know 𝑣, competition should drive price up to 𝑣.

Why Doesn’t Everyone Invest?#

A possible explanation is the winner’s curse. If some buyers are informed, then uninformed buyers will acquire more shares in undersubscribed IPOs with poor prospects while informed buyers acquire in the remaining IPOs. If informed betters earn supernormal profits and uninformed buyers earn normal profits, then the average return must be above normal ⇒ IPO shares are underpriced.

There are alternative explanations:

Investment banks set IPO prices low to cater to their clients.

Investment banks choose a low price to have control over who gets allocated shares and avoid any risk of undersell.

Perhaps well-designed IPO auction could aggregate information, but IPOs generally don’t use auctions.

Summary#

Bidder values can depend on both “private value” and “common value” factors. Focusing on the common value elements:

The event of winning reveals information about others’ estimates.

Sophisticated bidders account for this in their bidding.

Bidders without accurate information should be cautious when bidding against better-informed bidders.

With many bidders and dispersed information, the auction price can be a surprisingly good indicator of the item’s value.

Sellers can sometimes reduce the winner’s curse by the design of lots and/or by sharing information with bidders.