Auction Design and Applications#

Reserve Prices#

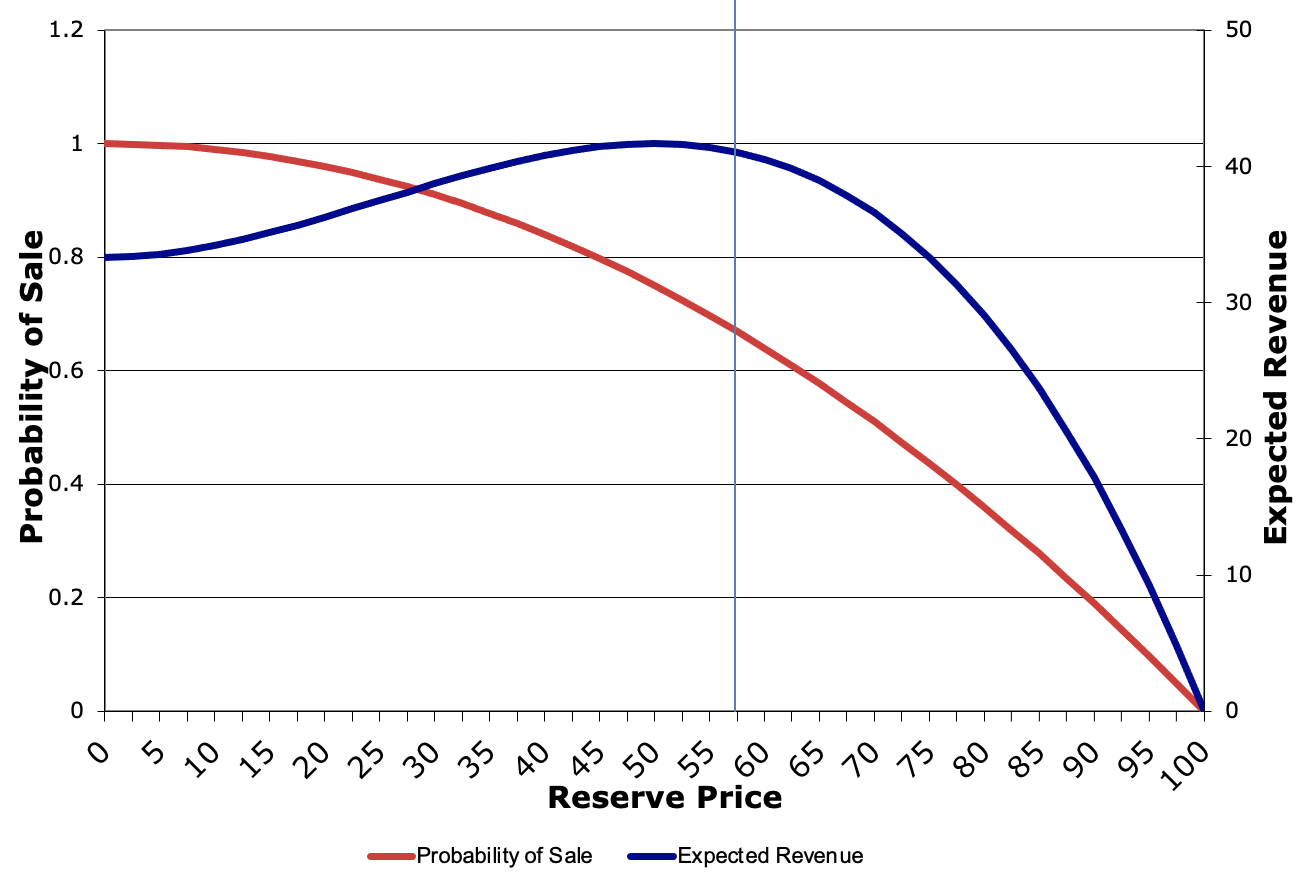

Two bidders with values \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) both drawn uniformly on \([0,100]\).

Question

Can the seller benefit from setting a “reserve” price, that is, a minimum price below which she won’t sell?

The seller sets a reserve price \(r\) and runs an ascending auction. The clock starts from \(r\) and goes up, so rational bidders with low values may decline to bid.

Three cases:

If both values are below \(r\), then no sale occurs.

If \(r\) is between both values, then the sale occurs at \(r\).

If both values are above \(r\), then the sale occurs at \(\min(v_1, v_2)\).

Revenue:

Use the law of total probability to calculate the expected revenue.

Event |

Probability |

\(\mathbb{E}[\text{Revenue}|\text{Event}]\) |

|---|---|---|

\(v_1, v_2 < r\) |

\(\frac{r}{100} \times \frac{r}{100}\) |

\(0\) |

\(v_i < r < v_j\) |

\(2\times\frac{r}{100}\times\left(1-\frac{r}{100}\right)\) |

\(r\) |

\(v_1, v_2 > r\) |

\(\left(1-\frac{r}{100}\right)\times\left(1-\frac{r}{100}\right)\) |

\(r+\frac{1}{3}\left(100-r\right)\) |

Expected revenue is a cubic function of \(r\):

Set \(\frac{d}{dr}\mathbb{E}[\text{Revenue}|r] = 0\). Two solutions. Maximum revenue is achieved at \(r^{*}=50\).

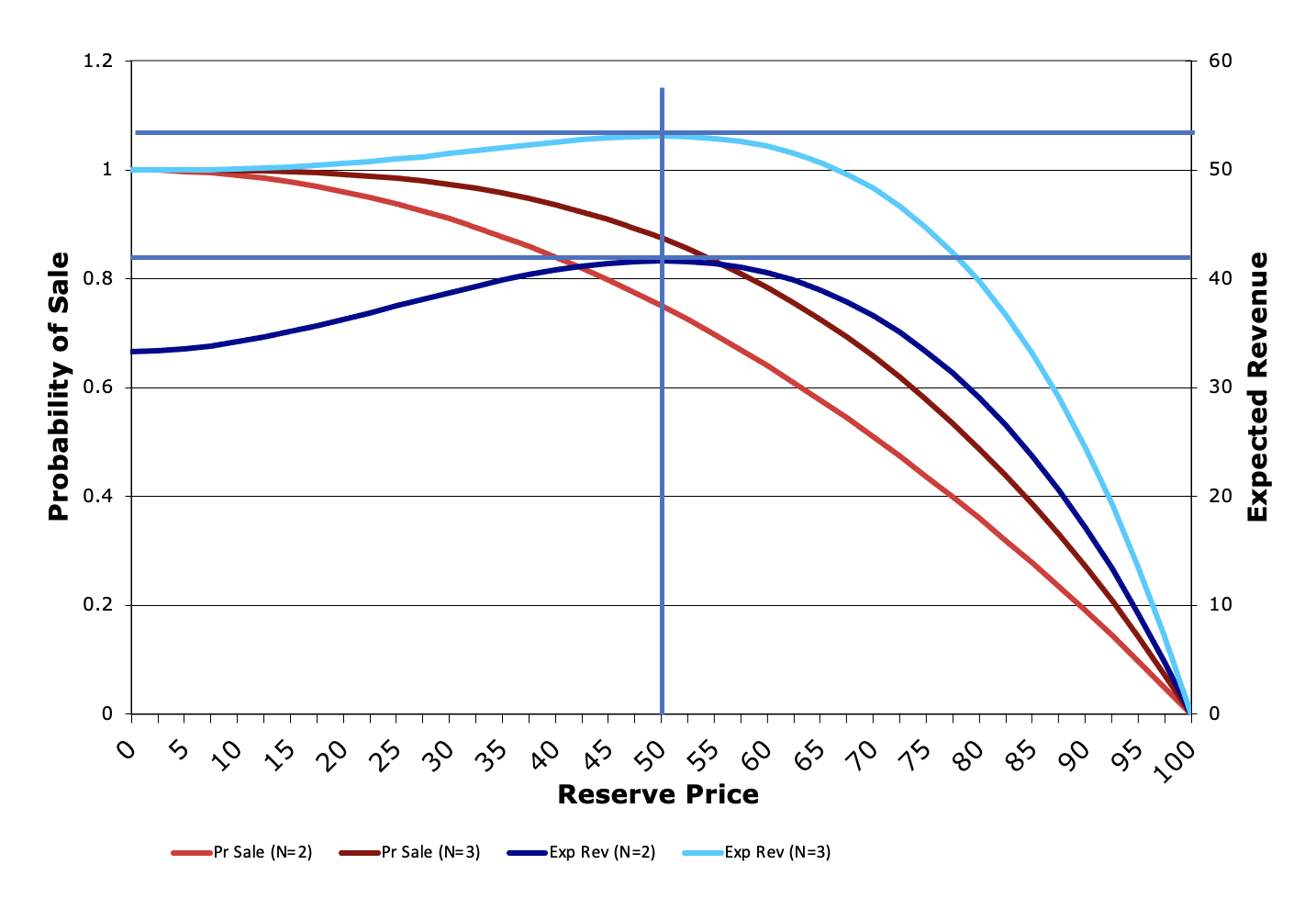

Fig. 2 Effect of Reserve with \(N=2,3\)#

Evidence on Reserve Prices#

Question

We’ve seen how reserve prices work in theory, but what about in practice? Does it help to set a higher reserve? Seems as if it might be hard to test.

At a used car auction, the BMWs will have higher reserve prices than the Chevys, but are also worth more.

Best evidence would be experimental - sell multiple versions of the same thing with different reserve prices.

Optimal Reserve Prices#

On eBay, the profit-maximizing reserve prices appear to be either

very low reserve price: maximizes probability of sale and encourages bidding competition to protect against a low-price outcome of auction.

very high reserve price: (close to item’s posted price) low chance of sale, but seller is guaranteed a good price if auction succeeds. In practice, sellers set either very low ($0.99) reserve prices or high reserve prices that effectively work as posted prices.

Bidder Subsidies and Set-Asides#

Question

In real-world auctions, it is common to see sellers choose to treat some bidders preferentially. Why?

For distributional reasons: e.g. state and federal procurement explicitly favors domestic, small or minority-owned businesses by restricting entry or giving subsidies.

For competition reasons: to “level” the playing field or encourage entry and create competition as in the case of attracting a “white knight” to a takeover battle.

Competition Policy#

Suppose the FCC plans to allocate \(N\) national licenses and bidders want to buy multiple licenses. How should we ensure that there are more than two major players in the industry after the auction?

Give “smaller” carriers an \(x\%\) discount?

Restrict each carrier to no more than \(x\) licenses?

Restrict largest carriers to \(x\) licenses in total?

Problem: how to choose \(x\) in each case! Set-asides provide more certainty about who wins, but we might end up with lower revenue.

“Optimal” Auction Design#

We’ve identified two ways to raise more revenue:

Reserve prices: withhold “quantity” to get a higher price.

Subsidies: favor weak bidders to get more competition.

General analysis of “optimal” or “revenue-maximizing” auctions (for which Roger Myerson won 2007 Nobel Prize):

Ascending auctions are efficient (high-value bidder wins), but

Sellers generally can benefit from distorting an auction away from efficiency in order to realize higher revenue (just like any monopolist!)

Practical Issues#

Our analysis has assumed

A fixed set of bidders willing to participate

Bidders behave competitively, or “non-cooperatively”

Practical auction design also has to worry about

Collusion - bidders may cooperate not compete

Entry - can be hard to get bidders to participate

Collusion#

Collusion occurs if bidders agree in advance or during the auction to let prices settle at a low level. This is generally illegal, but it can and does happen. Concern is often biggest (and can be less obviously illegal) when there are multiple items for sale: e.g. “you take those, I’ll take these – let’s end the auction.”

With a single item – collusion might rely on

Side agreements: you win today and share the profit with me.

Inter-temporal trades: you win today, I’ll win tomorrow

Example 7

U.S. v Pook (1988) quoted in Einav et al. [2015]

“When a dealer pool was in operation at a public auction of consigned antiques, those dealers who wished to participate in the pool would agree not to bid against the other members of the pool. If a pool member succeeded in purchasing an item at the public auction, pool members interested in that item could bid on it by secret ballot at a subsequent private auction (“knock out”) …. The pool member bidding the highest at the private auction claimed the item by paying each pool member bidding a share of the difference between the public auction price and the successful private bid. The amount paid to each pool member (“pool split”) was calculated according to the amount the pool member bid in the knock-out.”

Asker [2010]

“The ring used an internal auction or ‘knockout’ to coordinate bidding. Ring members would send a fax or supply a written bid to an agent (a New York taxi and limousine driver employed by the ring), indicating the lots in which they were interested, and what they were willing to bid for them in the knockout auction. The taxi driver would then collate all the bids, determine the winner of each lot, notify the ring as to the winners in the knockout and send the bids to another ring member who would coordinate the side payments after the target auction was concluded. Depending on who actually won the knockout, the taxi driver would, usually, either bid for the winner in the target auction, using the bid supplied in that auction as the upper limit, or organize for another auction agent to bid for the winner on the same basis. In the language of auction theory, the knockout was conducted using a sealed-bid format, with the winning bidder getting the right to own the lot should it be won by the ring in the target auction. The winning bid in the knockout set the stopping point for the ring’s bidding in the target auction. Since bidding in the target auction was handled by the ring’s agent, monitoring compliance with this policy was not a problem.”

Stamp Ring Mechanism#

Algorithm 14 (Stamp Ring Mechanism)

Bidders submit their offers to the ring auctioneer. High bidder, and high bidder only, enters main auction at his bid. If ring bidder wins, payments within the ring computed as follows

First, subtract main auction payment from all ring bids.

Throw away negative (net) bids that would have lost main auction.

Bidders who made positive bids get to share in the ring gains.

Look at “increment” from auction price up to first ring bid – divide among all ring participants (could be equal, or 50% to winner and then equal).

Then look at next “increment” and divide between all ring bidders who bid higher, and so forth.

Winner makes side payments to losers, so gains are split accordingly.

Example 8

Bidder |

Knockout Bid |

Bid Net of Main Auction Price |

Private Side Payment |

|---|---|---|---|

A |

\(400\) |

\(400 - 200 = 200\) |

Pay \(80\) |

B |

\(360\) |

\(360-200=160\) |

Receive \(55 = 25 + 30\) |

C |

\(300\) |

\(300 - 200 = 100\) |

Receive \(25 = 50/2\) |

D |

\(185\) |

\(185 - 200 = -15\) |

\(0\) |

Payment to Main Auction |

\(200\) |

First increment of 100, split between A, B, C (1/2 to winner) Second increment of 60 split equally between A,B. Last increment of 40 goes to A.

Deterring Collusion#

Question

What auction design works to deter collusion?

Suppose bidders A and B agree in advance that A should win at a low price. Although B can cheat on the agreement and keep bidding, there is little to gain, since A can just keep bidding. That possibility helps to enforce the agreement.

sealed bidding (first-price auction):

If A and B agree that A should win at a low price, A must bid low. If B cheats by making a slightly higher bid, it can win the auction at a low price. Makes it harder to sustain collusion.

Entry#

A typical problem in organizing auction sales is to make sure that enough bidders will participate. Auctions rely on having competition to set the price, and bidders may not want to participate unless they think they have a good chance.

Question

When might entry be a concern, and what can be done?

Example 9

Two bidders, values drawn from \(U[0,100]\) and \(U[0,200]\). How much profits should bidders expect from an ascending auction?

Half the time, bidder 2’s value is \(>100\). Then, bidder 1 always loses, so he earns \(0\). Bidder 2, on average, has a value of \(150\) and pays \(50\), so her average profit in this case is \(100\).

Half the time, bidder 2’s value is \(<100\). Then, our previous analysis applies. Bidders 1 and 2 each win half of those times with an average value of \(66\frac{2}{3}\) and pays an average price of \(33 \frac{1}{3}\), so the winner’s expected profit in these cases is \(33 \frac{1}{3}\).

Bidder 1’s expected profit is \(8 \frac{1}{3}=1/2 \times 1/2 \times 33 \frac{1}{3}\)

Bidder 2’s expected profit is \(58 \frac{1}{3} = 1/2 \times 100 + 1/2 \times 1/2 \times 33 \frac{1}{3}\)

If the cost of entry is \(10\), bidder 1 won’t even bother. And bidder 2 could end up winning at a price of zero!

Promoting Entry#

Subsidize weaker bidders: Encourages their participation - can also restrict very strong bidders from winning too much (a “set-aside” policy)

Subsidize entry costs directly: For example, in architectural competitions, architects may be reimbursed for building a model needed to submit a bid for the contract.

Sealed bidding: Prospect of very low prices in sealed bid auction encourages bidders to enter and try to “steal” the auction - whereas with open bidding, a strong bidder can respond to entry after it happens.

Bid Subsidies#

Suppose seller gives \(50\%\) discount to the weaker bidder (e.g., if weak bidder wins at a price of \(50\), only has to pay \(25\)).

What is the optimal weak bidder strategy? Bid up to \(2 v_1\) (at which point the “price” is really \(v_1\))

If watching the bidding, it will be “as if” both bidders have values drawn on \([0,200]\), rather than \([0,100]\) and \([0,200]\).

Question

What is the expected clock price and why are the two bidders equally likely to win?

Expected clock price is \(66 \frac{2}{3}\). Equal to the expected second highest of two random variables distributed uniformly on \([0,200]\), but expected revenue is lower, equal to \(50\). Why? Half the time, bidder 1 wins and pays only half its winning bid, so expected revenue is \(1/2 \times 66 \frac{2}{3}+1/2 \times 33 \frac{1}{3}=50\).

To Subsidize or Not Subsidize#

With no subsidy:

Strong and weak bidder win with probability \(3/4, 1/4.\)

Seller gets expected revenue of \(41 \frac{2}{3}\).

Auction is efficient: high value bidder wins.

With subsidy for weak bidder:

Strong and weak bidder win with probability \(\frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{2}\).

Seller gets expected revenue of \(50\). (Higher!)

Auction is inefficient: weak bidder may win with lower value!

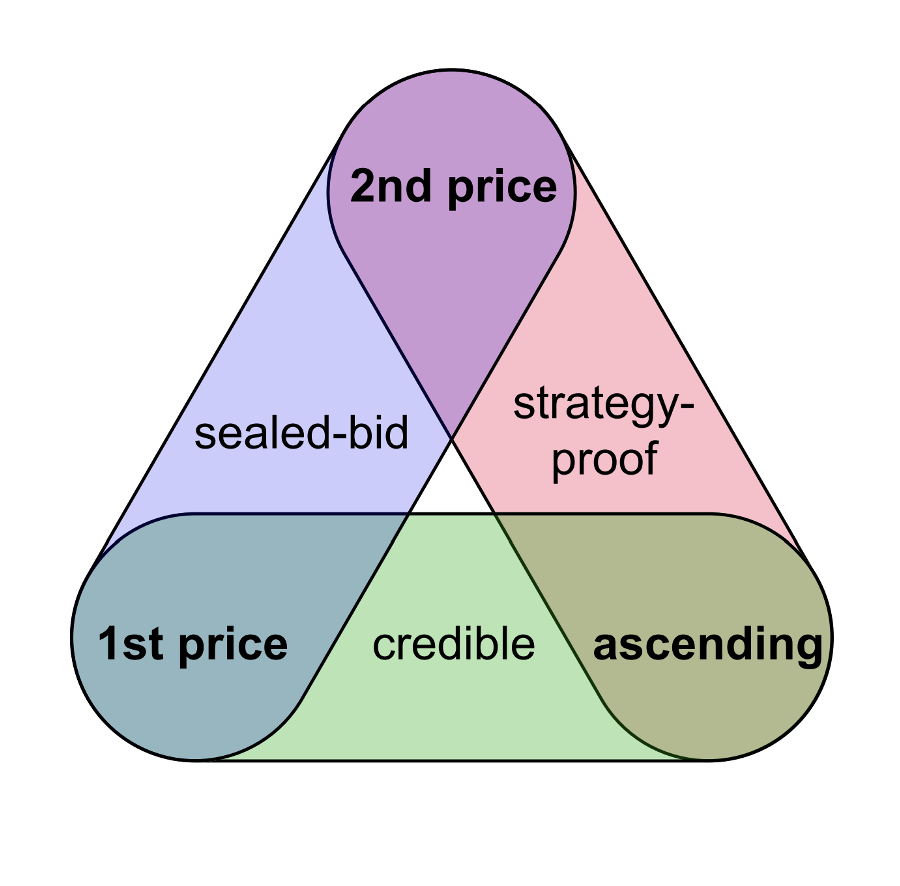

Credibility#

Consider the sealed-bid second-price auction. The bidders don’t see one another’s bids, so the winner has to take the seller’s word for it as to what the second highest bid was, but the seller might misreport the second highest bid.

- credible#

We call an auction mechanism credible if the seller never has an incentive to cheat secretly, deviating from the mechanism protocol in a way he can get away with, if bidders observe only their own choices and outcomes.

Three-Way Tradeoff#

Summary#

Auction design can involve multiple objectives

Efficiency: making sure high value bidder wins

Revenue: getting the best possible return on the sale

Distributional: favoring some bidders over others

There are often trade-offs among these objectives

Reserve prices and subsidies can sometimes increase revenue even though they may distort the auction away from efficiency.

Practical auction design must also worry about basic economic issues such as collusion and entry.