Sponsored Search Auctions#

Background#

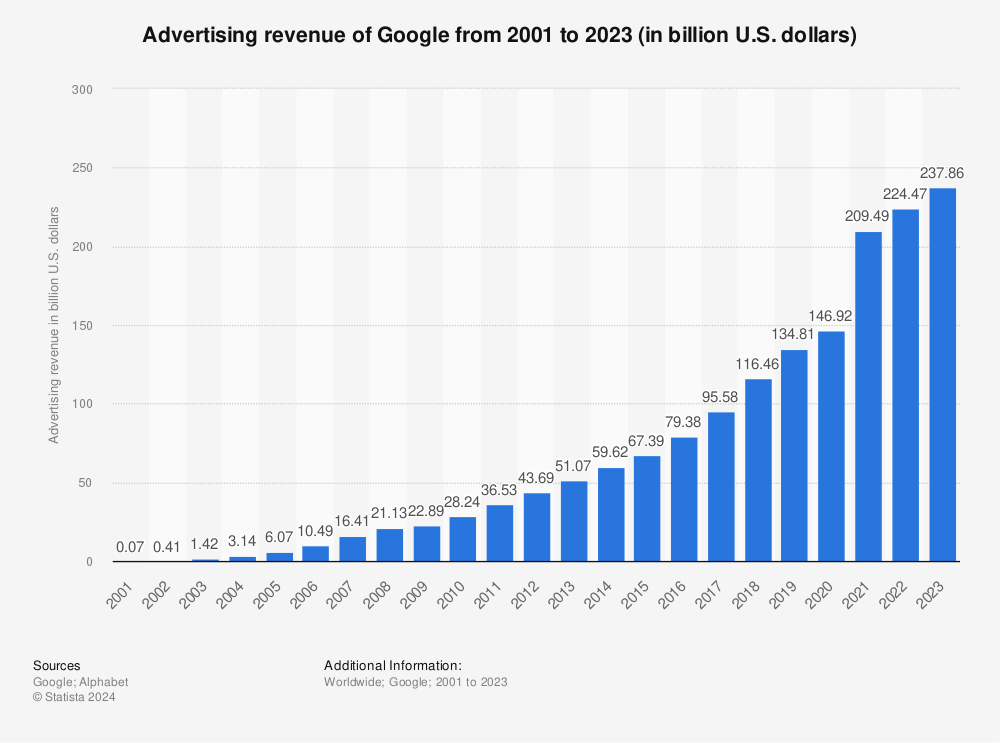

Find more statistics at Statista

Sponsored Search Auctions#

Search advertising is a huge auction market. In 2021, Google ad revenue in 2021 was $209 billion.

“Most people don’t realize that all that money comes pennies at a time.”

—Hal Varian, Google Chief Economist

Google auctions advertisement space on certain keywords in search queries. For example, local furniture stores may compete with one another for the top link on a search for “office desks.” Why use auctions instead of just setting prices? There are tens of millions of keywords, so it’s impractical to set so many prices. Demand and especially supply change frequently, and auctions retain some price-setting ability. Today, the theory and practice of these auctions is an application of the assignment market model!

Keyword Auctions#

Advertisers submit bids for keywords

Offer a payment per click.

Alternatives: per impression or per conversion.

Separate auction for every query

Positions awarded in order of bid (more on this later).

Google uses “generalized second price” format.

Advertisers pay bid of the advertiser in the position below.

Some important features

Value is created by getting a good match of ad to searcher.

Multiple positions, but advertisers submit only a single bid.

Brief History#

1990s: websites sell advertising space on a “per-eyeball” basis, with contracts negotiated by salespeople; similar to print or television.

Mid-1990s: Overture (GoTo) allows advertisers to bid for keywords, offering to pay per click. Yahoo! and others adopt this approach, charging advertisers their bids.

2000s: Google and Overture modify keyword auction to have advertisers pay minimum amount necessary to maintain their position (GSP).

Auction design becomes more sophisticated; auctions used to allocate advertising on many web pages, not just search.

Assignment Model (Variation)#

There are \(k = 1, \dots, K\) positions on the page and bidders \(n = 1, \dots, N\). Position \(k\) has “click rate” \(x_k\) where \(x_1 > x_2 > \dots > x_K\). Bidder \(n\) has value \(v_n\) per click: \(v_1 > v_2 > \dots > v_N\). So, bidder \(n\)’s value for position \(k\) is: \(v_{nk} = v_nx_k\). If bidder \(n\) buys \(k\) and pays \(p_k\) per click, it earns \((v_n - p_k) x_k\). An efficient (total-value maximizing) assignment gives position \(1\) to bidder \(1\), position \(2\) to bidder \(2\), etc.

Questions#

Two positions: receive \(200\) and \(100\) clicks per day. Bidders \(1, 2, 3\) have per click values \(10, 4, 2\).

Top |

Second |

|

|---|---|---|

Bidder \(1\) |

\(2000\) |

\(1000\) |

Bidder \(2\) |

\(800\) |

\(400\) |

Bidder \(3\) |

\(400\) |

\(200\) |

Find the efficient allocation and compute the total value it creates.

Solution

Bidder \(1\) gets the top position: value \(200 \times 10 = 2000\). Bidder \(2\) gets the second position \(100 \times 4 = 400\), so the efficient allocation creates value \(2400\).

Find the lowest market clearing price.

Solution

Bidder \(3\) demands nothing, so \(p_1 \geq 400\) and \(p_2 \geq 200\).

Bidder \(2\) buys the second position, so \(400 - p_2 \geq \max(0, 800 - p_1)\).

Bidder \(1\) buys the top position, so \(2000 - p_1 \geq \max(0, 1000 -p_2)\)

So, the Vickrey/lowest market clearing prices are \(600\) and \(200\) (graphing this on des)

Graph the set of market-clearing prices in terms of per click values.

Solution

Bidder \(3\) demands nothing: \(p_1, p_2 \geq 2\) Bidder \(2\) demands position \(2\): \(4 \geq p_2 \geq 2p_1 - 4\)

Prefers position \(2\) to nothing: \(100 \times (4 - p_{2}) \geq 0\)

Prefers position \(2\) to \(1\): \(200 \times (4 - p_{1}) \leq 100 \times (4 - p_{2})\) Bidder \(1\) demands position \(1\): \(2 p_1 \leq 10 - p_2\)

Prefers position \(1\) to \(2\): \(200 \times (10 - p_1) \geq 100 \times (10 - p_2)\)

Prefers position \(1\) to nothing: \(200 \times (10 - p_1) \geq 0\)

Algorithmic Min/Max Clearing Price Discovery#

We assume more bidders than positions, so \(N > K\).

Algorithm 16 (lowest clearing price discovery)

Set \(p_k = v_{K + 1}\) so that bidder \(K + 1\) won’t buy that position.

For \(k <K\), given \(p_{k+1}\), set \(p_k\) so that bidder \(k + 1\) will be just indifferent between buying position \(k+1\) and \(k\):

Algorithm 17 (_highest clearing price discovery)

Set \(p_k = v_{K}\) so that bidder \(K\) is just willing to buy.

For \(k <K\), given \(p_{k+1}\), set \(p_k\) so that bidder \(k + 1\) will be just indifferent between buying position \(k+1\) and \(k\):

Pay-As-Bid Auctions#

Pay-as-bid auctions are sometimes also called overture auctions.

Algorithm 18 (Pay-As-Bid Auctions)

Each bidder submits a single bid (in dollars per click)

Top bid gest position \(1\), second position \(2\), etc.

Bidders pay their bid for each click they get.

Pay-as-bid auctions are sometimes also called overture auctions.

Remark 7

The pay-as-bid auction is unstable.

Proof. Consider as before two positions that receive \(200\) and \(100\) clicker per day. Bidders \(1,2,3\) have per-click values \(10, 4, 2.\) Then running the pay-as-bid auction yields:

Bidder \(3\) will offer up to \(2\) per click

Bidder \(2\) must bid \(2.01\) to get second slot

Bidder \(1\) wants to bid \(2.02\) to get top slot.

But then bidder \(2\) wants to top this, and so on.

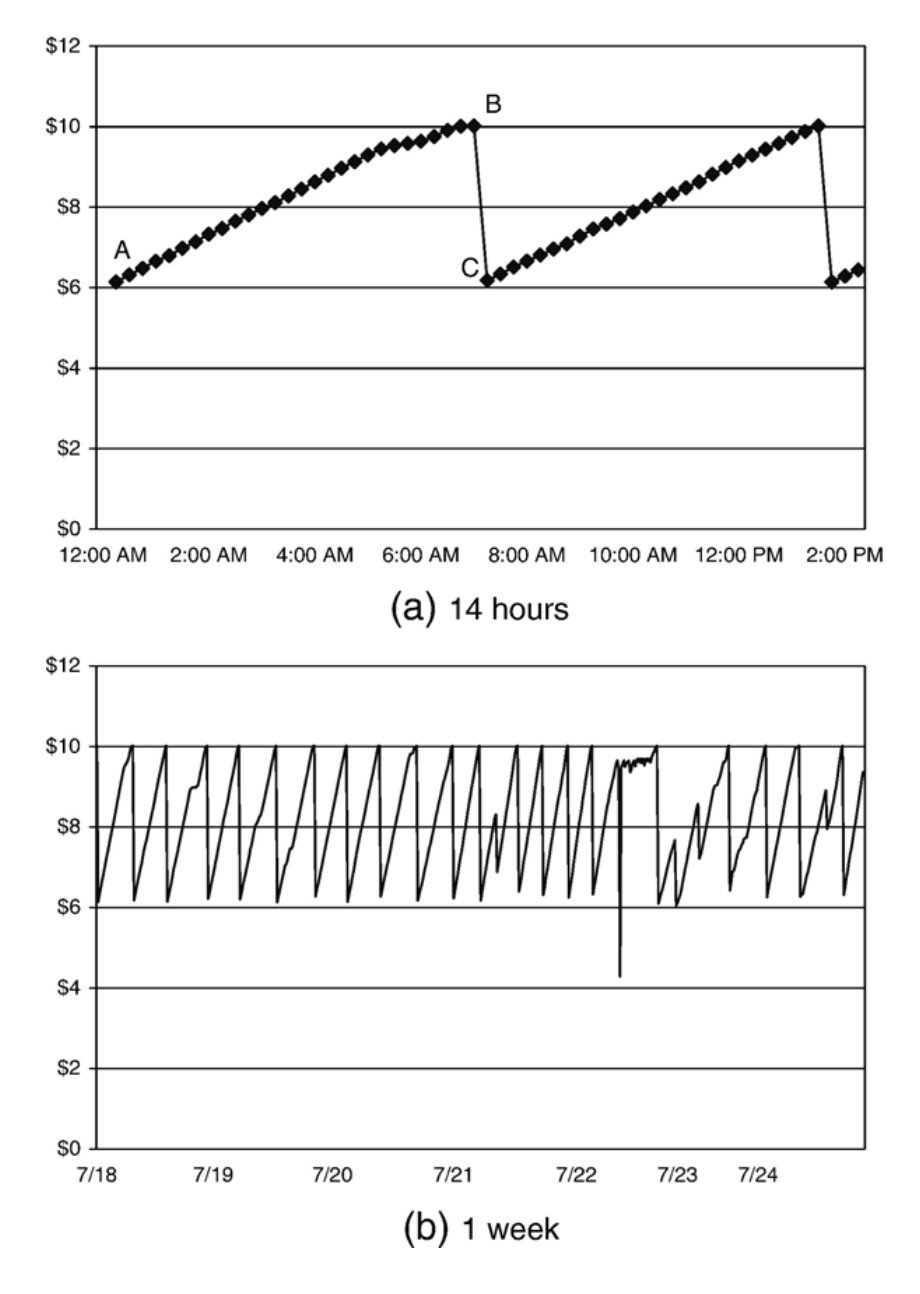

We also observe this instability in practice.

Fig. 4 A “sawtooth” pattern caused by auto-bidding programs. [Edelman and Ostrovsky, 2007]#

Google Generalized Second Price (GSP) Auctions#

Algorithm 19 (Generalized Second Price Auctions)

Bidders submit bids (in dollars per click)

Top bid gets slot \(1\), second bid gets slot \(2\), etc.

Each bidder pays the bid of the bidder below them.

Intuitively, this seems more stable than pay-as-bid auctions, but do the bidders want to bid truthfully?

Theorem 16

GSP auctions aren’t truthful.

Proof. Consider two positions with \(200\) and \(100\) clicks. Also consider a bidder with value \(v_1 = 10\). There are competing bids \(v_2 = 4\) and \(v_3 = 8\). If our bidder bids \(10\), they get the top position and pay \(8\) and profit \(200 \times 2 = 400\). However, if they bid below their value at \(5\), then they win the second position and pay \(4\), so their profit is \(100 \times 6 = 600\). So, bidding untruthfully is more profitable.

Note that the GSP isn’t always untruthful. If the competing bids were instead \(6\) and \(8\), then the dominant action for the bidder would have been to bid truthfully at \(10\).

See also

Get more practice here!

Finding GSP Equilibria#

Fix any set of market clearing per-click prices: \(p_1, \dots, p_N\). Assume that \(N > K\). There is a GSP equilibrium in which:

Bidder 1 bids any amount more than \(p_1\)

Bidder 2 bids \(p_1\)

Bidder 3 bids \(p_2\).

etc. Bidder \(k\) will prefer to buy position \(k\) and pay \(p_k\) rather than buy position \(m\) and paying \(p_m\) – that’s why the prices were market clearing!

Vickrey Auction#

Algorithm 20 (Vickrey auction)

Bidders submit bids (dollars per click)

Seller selects the assignment that maximizes total value

Puts highest bidder in top position, next in 2nd slot, etc.

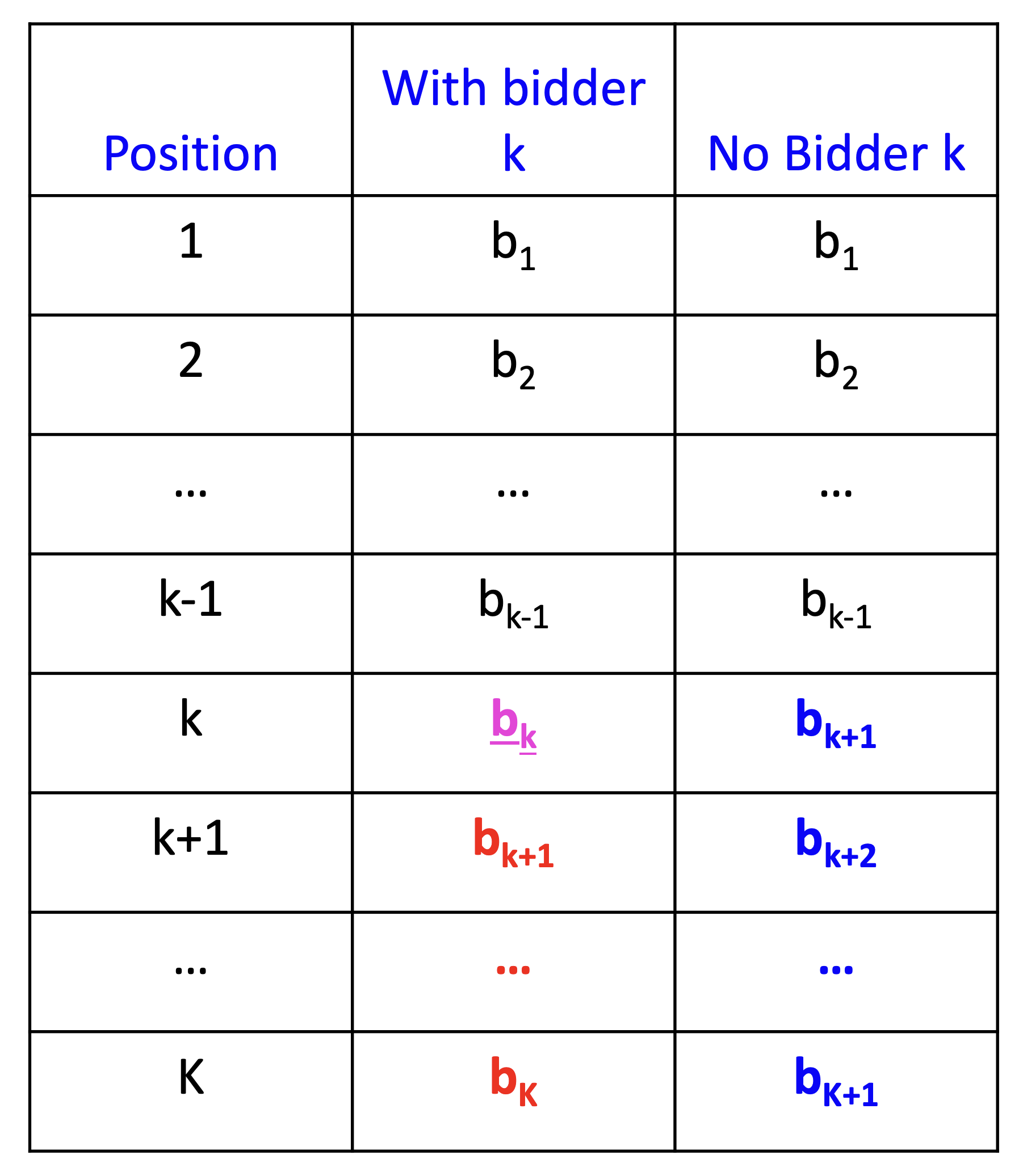

Charges any winner the total value that its bid displaces.

For bidder \(n\), each bidder below \(n\) is displaced by one position, so must add up the value of all these “lost” clicks.

Dominant strategy to bid one’s true value. Facebook uses a Vickrey auction.

Pricing#

Order per-click bids: \(b_1 > b_2 > \dots > b_K\)

Consider bidder who wins \(k\)th slot.

Displaces \(k+1, \dots, K\)

Leaves \(1, \dots, k - 1\) intact. Displaced bidder \(j\) would get \(x_{j-1}\) clicks in position \(j-1\), but instead gets \(x_j\) clicks in position \(j\). \(k\)’s Vickrey price is \(\sum_{j > k} b_j(x_{j-1} - x_j)\).

Note

In GSP, bidder \(k\) pays: \(b_{k+1}x_k\)

The Vickrey (VCG) Formula#

In the Vickrey, if a bidder wins, then it pays the resulting “opportunity cost.”

Payment = the loss of value to others caused by the change.

Consequence: A bidder prefers the efficient allocation.

The VCG “pivot” mechanism extends and generalizes that idea.

The problem is to choose some decision \(x \in X\) from a finite set.

Each participant \(n\) reports a value function \(v_n: X \to \mathbb{R}_+\)

Mechanism selects \(x^*\) to solve \(\max_{x \in X}\sum_n v_n(x)\).

Without \(j\), the mechanism would select \(x_j^∗\) to \(\max_{x \in X}\sum_{n \neq j} v_n(x)\).

VCG pivot mechanism: \(j\) pays \(\sum_{n \neq j}(v_n(x_j^*) - v_n(x^*))\)

That is, \(j\) pays for any loss she causes to others, so she prefers to cause a loss only when her own benefit is larger!

Summary of Results#

Result 1. The generalized second price auction (GSP) does not have a dominant strategy.

Result 2. The Nash Equilibria of the GSP are “equivalent” to the set of competitive equilibria[1]: Bidders obtain their surplus-maximizing positions For any NE of the GSP, the prices paid correspond to market clearing prices, and for any set of market clearing prices, there is a corresponding NE of GSP.

Result 3. The Vickrey auction is truthful and its payments in the position auction are equal to the lowest market-clearing prices.

Keyword Auction Design#

Platforms can exercise some control over prices

Restricting the number of slots can increase prices.

Setting a reserve price can increase prices

Platforms can also “quality-adjust” bids

In practice, ads that are more “clickable” get promoted.

Bids can be ranked according to bid * quality.

This gives an advantage to high-quality advertisements.

Sponsored vs Organic Results#

Google and Bing show “organic” search results on the left side of the page and “sponsored” results above or on the right.

The assignment of positions on the page is different

Organic search results: use algorithm to assess “relevance”

Sponsored search results: use bids to assess “value”

To some extent there is competition: if a site gets a good organic position, should it pay for another? Search engines have to think about maximizing user experience but also about capturing revenue from advertisers.

Summary#

Search auctions create a real-time market in which advertising opportunities are allocated to bidders.

Auction theory suggests that the “generalized second-price” rules used in practice might be reasonably efficient.

GSP is not “truthful” but it has efficient Nash equilibria with competitive prices.

Vickrey auction is truthful but more complicated.

In practice, the search platforms have some scope to engage in optimal auction design.